We humans are linear. We love our straight lines and do our best to find them wherever we look. We like straight roads, straight pillars, tall buildings and straight edges on paper. We try to find straight lines in our scientific endeavors. Sometimes it works, and sometimes the match is way out of line—that pun was unintentional, but I’ll keep it since it works.

The stunning rhythms in architecture that consist of straight lines and sharp angles are a joy to view. The colonnade of St. Peter’s Basilica, the Parthenon, a structure by Mies van der Rohe and thousands of other buildings around the world are hypnotizing and seem to reflect a higher order of nature.

But these structures become boring quickly if all we use are straight lines and sharp angles. Eventually we put in a curve here and there to add variety. We add curves because it seems more natural to do that. We know that Nature does not drum a monotonous beat. Too much of the same pattern and we have dreary, staid and lifeless.

Intuitively, we know that Nature is not linear, even though we force her into our straight lines and often get confused when she goes her own, unpredictable way. When wind suddenly changes direction or whirls into a tornado we say the effect was unexpected. We want nature to play nice and thus confuse the map (our beliefs and science) with the territory (Nature.)

We love our strait lines, but the truth is, we also know they’re not quite right. We live in the delicate balance between variety and sameness; we want both a stable relationship and a fiery romance. But the stable relationship gets tedious and the fiery romance quickly fades. We want our Aristotelean mean but never reach it because the mean is not a real entity, but rather just an average of the fluctuations between extremes. Average is a mental state. And it is no surprise that Nature has no average.

Athroisis: Things come together

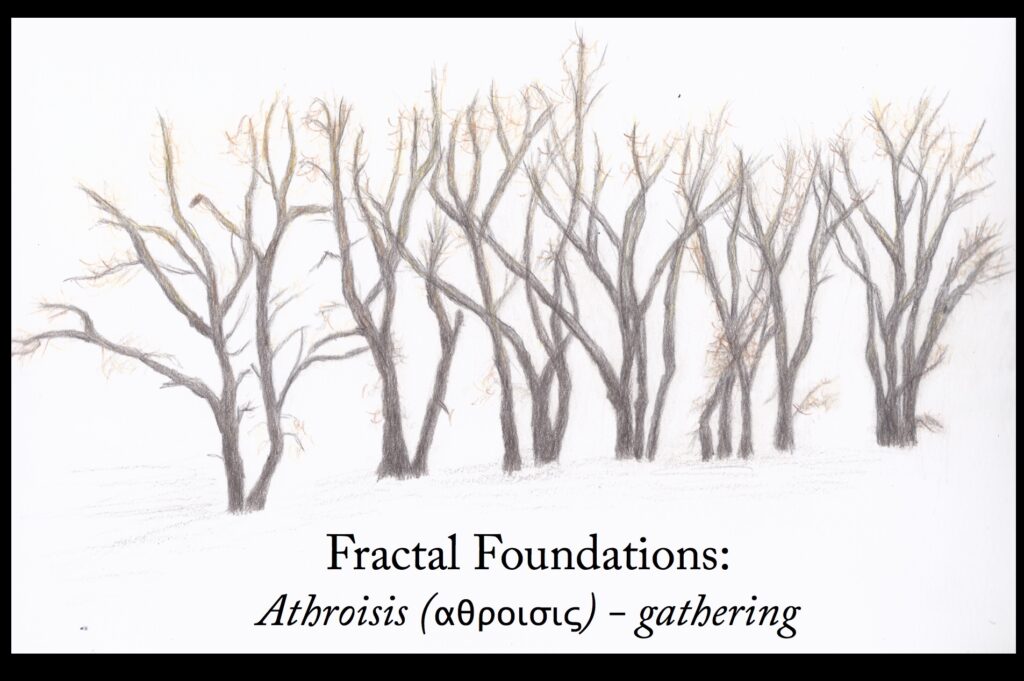

Nature lives on that boundary of sameness and variety. One such example is what I call Athroisis (pronounced a-THROY-sis), which is Greek for « a gathering process. » (Special thanks to Dr. Richard Martin of Stanford University who helped me with the proper word choice.) When you see objects in nature gather together, they don’t align in perfect squares or circles, they cluster together in a loose arrangement where the number in each cluster is usually different. Sometimes, the cluster will be small, even a cluster of one. Other times the clusters are made up of thousands of individual items.

We find athroisis everywhere in nature. A forest grove, when looked at from above or from a distance, reveals trees interspersed in groups. A pile of leaves on the ground form clumps. The petals on a flower are not completely symmetrical; sometimes they shift a bit to the side. Mountain peaks, river deltas and even spots on a leaf cluster together. We know instinctively that planting our garden requires groupings. An array of flowers and shrubs regularly distributed just seems, unnatural.

A chaos scientist would call athroisis, a strange attractor. An attractor is a point of equilibrium in a system (see page: What is Fractal Design?) A strange attractor is a system where things never quite settle down. There is a sort of equilibrium, but it isn’t stable. And that is what we see in nature. As a system that always in flux, there is never a chance for natures creations to settle down.

One might think that I’m looking for something that really isn’t a phenomenon. After all, the reason plants cluster together is because of seeds, wind patterns, whether or not it is a rhizome and other variables. A river delta is based on the level of the ground.

I argue that the cause is immaterial. The effect is everywhere, so much that we should pay attention to it in our art.

Athroisis in Art

And we do use athroisis in our art. We feel it naturally in our music. We place our songs in a musical key but deviate from that with dissonance. A composition has a theme, but it morphs into different rhythms and slightly different notes. Dancers whirl and twirl across the stage, gathering together for a moment only to break apart and rejoin in a new formation.

We can apply athroisis to design principles just as easily. We can accent our tables and chairs with varying clusters. Chair backings can be composed of varying slats. An end table could vary the number of legs. Le Corbusier used athroisis in two of his buildings: Couvent de la Tourette and Carpenter Center. If you look closely at his windows, you’ll notice varying widths.

Notice the fenestration along the second and third floors

Notice the fenestration along the curved studio space

Groupings are not merely cosmetic. They can be the foundation of a structure. For example, we can design colonnades in groups that vary in distance. Pillars inside of a building can also be grouped. The structure will change to accompany the placement of the pillars. The initial placement of the pillars will determine the levels above it. This can lead to exciting variations in a building’s look merely by the arrangement of the pillars at ground level. This dependence on the initial placement of load-bearing columns is what I call iteration, and it’s a critical component of Fractal Design and fractals in general.

Do not think this is a radical departure from conventional design. I stated earlier that sameness and linearity are critical. Athroisis, and Fractal Design in general are meant to work harmoniously with linear design. When we’re grounded in regularity we can soar to greater heights. Just as we can see that the trees in the forest are « regular but different », we can design with the same principle. In another post I will discuss how to vary athroisis with linear design.